Cell lysis

The initial step in DNA extraction is cell lysis, which involves breaking open the cells to release their contents, including the DNA. The choice of lysis method depends on the sample type, with considerations for cell wall composition and the fragility of the genetic material.

Caution

This page is a work in progress and is subject to change at any moment.

Chemical lysis

Chemical lysis is a fundamental technique in DNA extraction protocols, employing various chemical agents to disrupt cell membranes and release intracellular contents, including nucleic acids. This method is widely used due to its efficiency, reproducibility, and applicability to a broad range of cell types.

Chemical lysis operates by destabilizing the lipid bilayer of cell membranes and denaturing proteins. This process compromises the structural integrity of the cell, leading to the release of cellular components, including DNA, RNA, and proteins, into the surrounding solution.

Detergents

In the field of molecular biology, particularly in DNA extraction procedures, detergents play a crucial role in cell lysis. Understanding how these molecules function is essential for grasping the fundamental principles of sample preparation in DNA sequencing and other molecular techniques.

Detergents are remarkable molecules with a unique structure that makes them invaluable in cell lysis protocols. At their core, detergents are amphipathic, meaning they possess both hydrophilic (water-loving) and hydrophobic (water-fearing) regions. This dual nature is key to their function.

- The hydrophilic head of a detergent molecule interacts favorably with water,

- while its hydrophobic tail, typically a hydrocarbon chain, avoids water interactions.

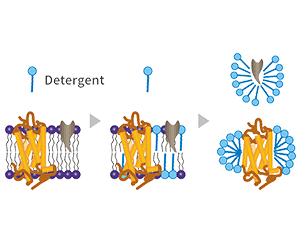

When introduced to a cellular environment, detergents begin their work by integrating themselves into the lipid bilayer of the cell membrane. The hydrophobic tails of the detergent molecules mingle with the fatty acid chains of the membrane lipids, while their hydrophilic heads remain exposed to the aqueous environment both inside and outside the cell. As more detergent molecules incorporate into the membrane, they initiate a process of micelle formation.

Micelles are spherical structures formed when the hydrophobic tails of detergent molecules cluster together to avoid water, with the hydrophilic heads facing outward. In the context of cell lysis, these micelles begin to include not just detergent molecules but also components of the cell membrane. This process marks the beginning of membrane solubilization.

At a specific detergent concentration known as the critical micelle concentration (CMC), the membrane’s structural integrity begins to fail. The lipids and proteins that once formed the cell’s protective barrier are now incorporated into detergent micelles. This solubilization of the membrane effectively creates holes in the cell’s outer layer, leading to the release of cellular contents, including the all-important DNA, into the surrounding solution.

However, the action of detergents isn’t limited to membrane disruption. Many detergents, particularly ionic ones like sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), also interact with and denature proteins. This process occurs as the hydrophobic tails of detergent molecules interact with the hydrophobic regions of proteins, which are typically buried in the protein’s interior. These interactions cause proteins to unfold, exposing more of their hydrophobic regions. The result is often a loss of protein structure and function, which can be beneficial in DNA extraction as it helps to separate DNA from its associated proteins.

The efficiency of detergent-mediated cell lysis depends on several factors. The concentration of the detergent is crucial and must be above the CMC for effective lysis. Temperature also plays a role, with higher temperatures generally increasing lysis efficiency, although excessive heat can risk DNA degradation. The ionic strength of the solution and its pH can affect how detergents interact with cellular components, thereby influencing lysis effectiveness. Additionally, different cell types, with their varying membrane compositions, may respond differently to detergent lysis, necessitating optimized protocols for different sample types. Understanding these mechanisms allows researchers to fine-tune their lysis protocols. For instance, when working with mammalian cells, which are generally more susceptible to detergent lysis, a gentler approach might be used. In contrast, bacteria, especially gram-positive species with their robust cell walls, might require stronger detergents or a combination of detergent and enzymatic treatment for effective lysis.

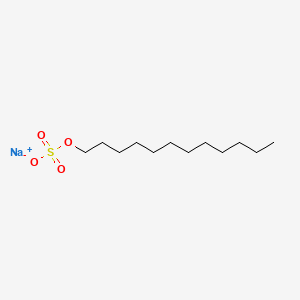

=== “Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS)”

An anionic detergent that is particularly effective in disrupting cell membranes and denaturing proteins.

!!! quote ""

<figure>

</figure>

SDS works by:

- Binding to and denaturing proteins, disrupting protein-lipid interactions.

- Solubilizing membrane lipids, leading to membrane disintegration.

- Typical concentrations range from 0.1% to 1% (w/v).

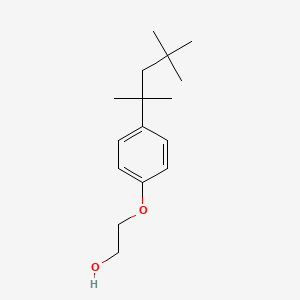

=== “Triton X-100”

A non-ionic detergent that is gentler than SDS and often used for isolating membrane-bound proteins.

!!! quote ""

<figure>

</figure>

- It can solubilize membranes without significantly denaturing proteins.

- Typically used at concentrations of 0.1% to 2% (v/v).

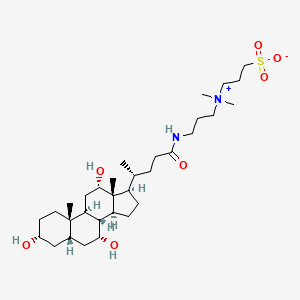

=== “CHAPS”

A zwitterionic detergent that is effective for membrane protein solubilization.

!!! quote ""

<figure>

</figure>

- It maintains protein activity better than SDS.

- Commonly used at concentrations of 0.5% to 2% (w/v).

Chaotropic Agents

Chaotropic agents disrupt the hydrogen bonding network between water molecules, affecting the stability of other molecules in the solution.

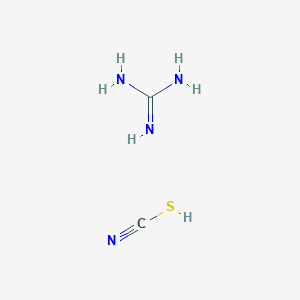

=== “Guanidinium Thiocyanate”

A potent protein denaturant and cell lysis agent.

!!! quote ""

<figure>

</figure>

- It rapidly solubilizes cellular components and inactivates nucleases.

- Typically used at high concentrations (4-6 M).

- Often combined with phenol in the guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction method.

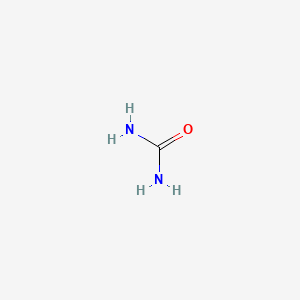

=== “Urea”

Another chaotropic agent used for cell lysis and protein denaturation.

!!! quote ""

<figure>

</figure>

- Less potent than guanidinium thiocyanate but still effective.

- Typically used at concentrations of 6-8 M.

Considerations

- Cell Type Specificity: Different cell types may require different lysis conditions. For example:

- Mammalian cells are generally more susceptible to detergent lysis than bacteria.

- Gram-positive bacteria, with their thick peptidoglycan layer, may require stronger lysis conditions or additional enzymatic treatment.

- pH and Ionic Strength: The efficiency of chemical lysis can be influenced by pH and salt concentration. Optimizing these parameters can improve lysis efficiency and DNA yield.

- Temperature: Some lysis protocols may require elevated temperatures (50-70°C) to increase the efficiency of membrane disruption and protein denaturation.

- Downstream Applications: The choice of lysis method should consider potential interference with subsequent steps in the DNA preparation process. For instance:

- SDS can inhibit some enzymatic reactions and may need to be removed before certain downstream applications.

- Chaotropic agents may need to be diluted or removed before DNA amplification or sequencing.

- DNA Integrity: While chemical lysis is generally less harsh than mechanical methods, prolonged exposure to harsh chemicals or elevated temperatures can lead to DNA degradation. Protocols should be optimized to minimize this risk.

- Combinatorial Approaches: Chemical lysis is often combined with other methods for enhanced efficiency:

- Enzymatic treatment (e.g., lysozyme for bacterial cells) followed by detergent lysis.

- Mild detergent treatment combined with mechanical disruption for tough-to-lyse samples.

By carefully selecting and optimizing chemical lysis conditions, researchers can efficiently disrupt cell membranes and release DNA, setting the stage for subsequent purification steps in the DNA sequencing sample preparation workflow.

Enzymatic lysis

Employs enzymes like lysozyme to break down cell walls, particularly effective for bacterial samples.

Mechanical disruption

Involves physical methods such as sonication, bead-beating, or freeze-thaw cycles to rupture cell membranes.