Procedure overview

Dideoxynucleotides

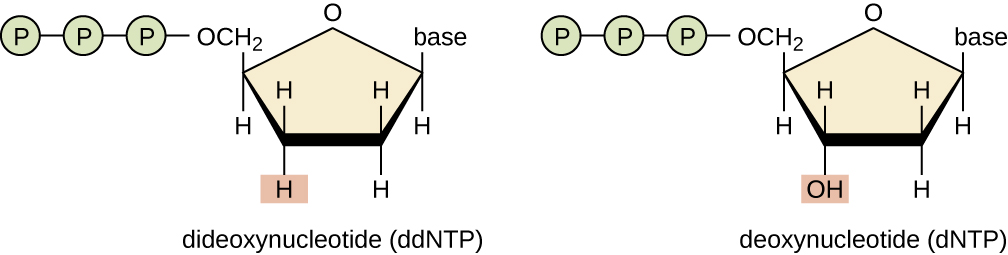

The use of dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) as chain terminators was a critical insight in the development of the method. This lack of hydroxyl group prevents ddNTPs from making a phosphodiester bond with the next nucleotide, thus terminating the nucleotide chain.

Respective ddNTPs of dNTPs terminate the chain at their respective site. For example, ddATP terminates at the A site, ddCTP at the C site, ddGTP at the G site, and ddTTP at the T site.

PCR

The sequencing begins by dividing the DNA sample into four separate reactions, each containing all four standard deoxynucleotides (dATP, dGTP, dCTP, and dTTP) and the DNA polymerase enzyme. In these reactions, only one type of dideoxynucleotide (ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, or ddTTP) is added to each reaction alongside the regular deoxynucleotides.

As the DNA polymerase extends the DNA chain during each sequencing reaction, termination occurs at different positions depending on which dideoxynucleotide is present. This results in the production of a series of DNA fragments of varying lengths in each reaction.

The termination at specific bases generates a unique pattern of fragments in each reaction. These fragments represent the particular nucleotide positions in the original DNA sequence. Using different dideoxynucleotides in separate reactions allows the researcher to obtain information about the sequence at each position along the DNA template.

Credit: Millipore Sigma

Fluorescence

The addition of fluorescent tags to dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) facilitates the detection and determination of DNA sequences. Each ddNTP (ddATP, ddGTP, ddCTP, or ddTTP) is labeled with a distinct fluorescent tag.

{ alight=left width=600 }

This labeling allows the simultaneous sequencing of DNA fragments from four separate reactions. After the DNA fragments are generated and separated by size through gel electrophoresis, adding fluorescent tags enables researchers to visualize and distinguish the terminated fragments based on their specific ddNTP. Automated sequencing machines can detect the color-coded fragments, providing a faster and more accurate means of determining the DNA sequence. This fluorescence-based approach enhances sensitivity and precision and reduces ambiguity in reading sequences. The use of fluorescently labeled ddNTPs has become a standard practice in Sanger sequencing, particularly in high-throughput sequencing projects, contributing to the efficiency and automation of the sequencing process.

Gel electrophoresis detection

TODO:

From Theory to Practice

Translating these ideas into a working method required overcoming numerous technical challenges, such as:

- Finding the right balance of dNTPs and ddNTPs

- Developing efficient separation techniques

- Creating sensitive detection methods (initially using radioactive labels, later fluorescent tags)

The elegance of Sanger sequencing lies in how it leverages fundamental principles of DNA structure and replication to solve the complex problem of determining nucleotide sequences. This method, born from careful reasoning and innovative thinking, revolutionized molecular biology and laid the groundwork for the genomic era.