Sequence alignment

In bioinformatics, a sequence alignment is a way of arranging two or more sequences of DNA, RNA, or protein to identify regions of similarity that may be a consequence of functional, structural, or evolutionary relationships between them. In many cases, the input set of query sequences are assumed to have an evolutionary relationship by which they share a linkage and are descended from a common ancestor. Aligned nucleotide or amino acid residue sequences are typically represented as rows within a matrix. Gaps are inserted between the residues to align identical or similar characters in columns. A pairwise alignment aligns two sequences, while a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) aligns three or more.

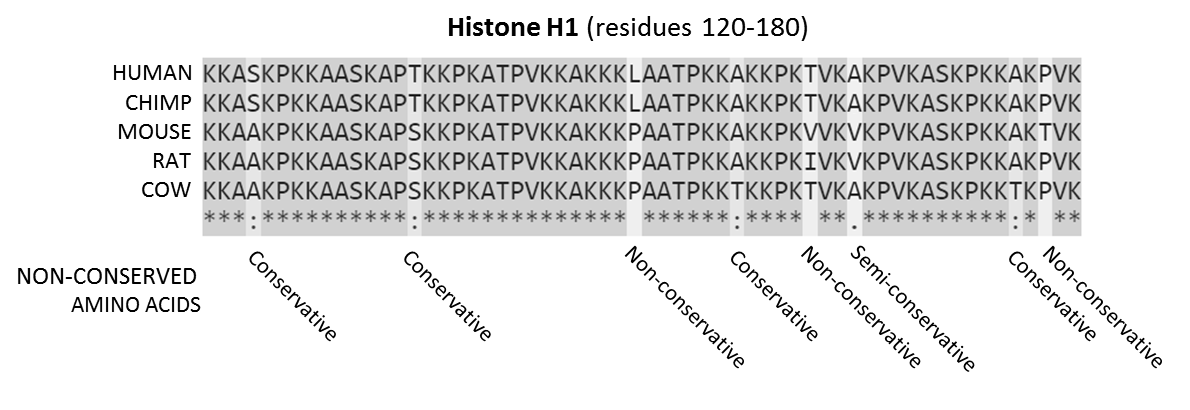

A multiple sequence alignment of mammalian histone proteins. Sequences are the amino acids for residues 120-180 of the proteins. Residues that are conserved across all sequences are highlighted in grey. Below the protein sequences is a key denoting conserved sequence (*), conservative mutations (:), semi-conservative mutations (.), and non-conservative mutations ( ). Conservative mutations produce chemically similar amino acids, while non-conservative mutations result in chemically distant residues.

Credit: Wikipedia.

Homology

In biology, homology is similar due to shared ancestry between structures or genes in different taxa. A typical anatomical example of homologous structures is the forelimbs of vertebrates, where the wings of bats and birds, the arms of primates, the front flippers of whales, and the forelegs of four-legged vertebrates like dogs and crocodiles are all derived from the same ancestral tetrapod structure. Evolutionary biology explains homologous structures adapted to different purposes due to descent with modification from a common ancestor.

Sequence homology between protein or DNA sequences is similarly defined in terms of shared ancestry. Two segments of DNA can have shared ancestry because of either a speciation event or a gene duplication event. Homology among proteins or DNA is inferred from their sequence similarity. Significant similarity proves that two sequences are related by divergent evolution from a common ancestor. Alignments of multiple sequences are used to discover homologous regions.

Interpretation

Suppose two sequences in an alignment share a common ancestor. In that case, mismatches can be interpreted as point mutations and gaps as indels (insertion or deletion mutations) introduced in one or both lineages in the time since they diverged from one another. In protein sequence alignments, the degree of similarity between amino acids occupying a particular position in the sequence can be interpreted as a rough measure of how conserved a particular region is among lineages. The absence of substitutions, or the presence of only very conservative mutations (that is, the substitution of amino acids whose side chains have similar biochemical properties) in a particular region of the sequence, suggests that this region has structural or functional importance.

Conserved sequences

In evolutionary biology, conserved sequences are identical or similar in nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) or proteins across species, within a genome, or between donor and receptor taxa. Conservation indicates that a sequence has been maintained by natural selection, likely because mutations in the sequence dramatically harm the organism’s health and fitness.

A highly conserved sequence has remained relatively unchanged far back up the phylogenetic tree and far back in geological time. Examples of highly conserved sequences include the RNA components of ribosomes, which are present in all domains of life, the homeobox sequences widespread among eukaryotes, and the tmRNA in bacteria. The study of sequence conservation overlaps with the fields of genomics, proteomics, evolutionary biology, phylogenetics, bioinformatics, and mathematics.

Just because two sequences are similar does not mean that the sequence has been conserved and the sequences are homologs. Convergent evolution can result in two unrelated sequences becoming similar. In some cases, two sequences can code for proteins or parts of proteins with similar functions but with no shared evolutionary history.

MSA of the seven Drosophila caspases colored by motifs. Note the long stretches of gaps (-) required to align the sequences.

Global and local alignments

Global alignments, which attempt to align every residue in every sequence, are most valuable when the sequences in a set are similar and of roughly equal size. (This does not mean global alignments cannot start and/or end in gaps.) Local alignments are more useful for dissimilar sequences suspected to contain relatively small regions of similarity or similar sequence motifs within their larger sequence context.

Multiple sequence alignment

Multiple sequence alignment extends pairwise alignment to incorporate more than two sequences simultaneously. Multiple alignment methods try to align all sequences in a given query set. Multiple alignments are often used in identifying conserved sequence regions across a group of sequences hypothesized to be evolutionarily related. Such conserved sequence motifs can be used in conjunction with structural and mechanistic information to locate enzymes’ catalytic active sites. Alignments are also used to establish evolutionary relationships by constructing phylogenetic trees. Multiple sequence alignment is often used to assess sequence conservation of protein domains, tertiary and secondary structures, and even functionally significant individual amino acids or nucleotides.

Multiple sequence alignment also refers to aligning a set of sequences. MSAs require more sophisticated methodologies than pairwise alignment because they are more computationally complex. Multiple sequence alignments are computationally tricky, one of the original challenges tackled by computational biologists. The utility of these alignments in bioinformatics has led to the development of various methods suitable for aligning three or more sequences.

Consensus sequences

MSAs allow the determination of a consensus sequence. In molecular biology and bioinformatics, the consensus sequence (or canonical sequence) is the calculated sequence of most frequent residues, either nucleotide or amino acid, found at each position in a sequence alignment. Consensus sequences are often printed at the bottom of MSAs and can be elaborated on using sequence logos (see below). Developing software for pattern recognition is a significant topic in genetics, molecular biology, and bioinformatics. Specific sequence motifs can function as regulatory sequences controlling biosynthesis or signal sequences directing a molecule to a specific site within the cell or regulating its maturation. Since these sequences have an essential regulatory function, they are thought to be conserved across long periods of evolution. In some cases, evolutionary relatedness can be estimated by the amount of conservation of these sites.

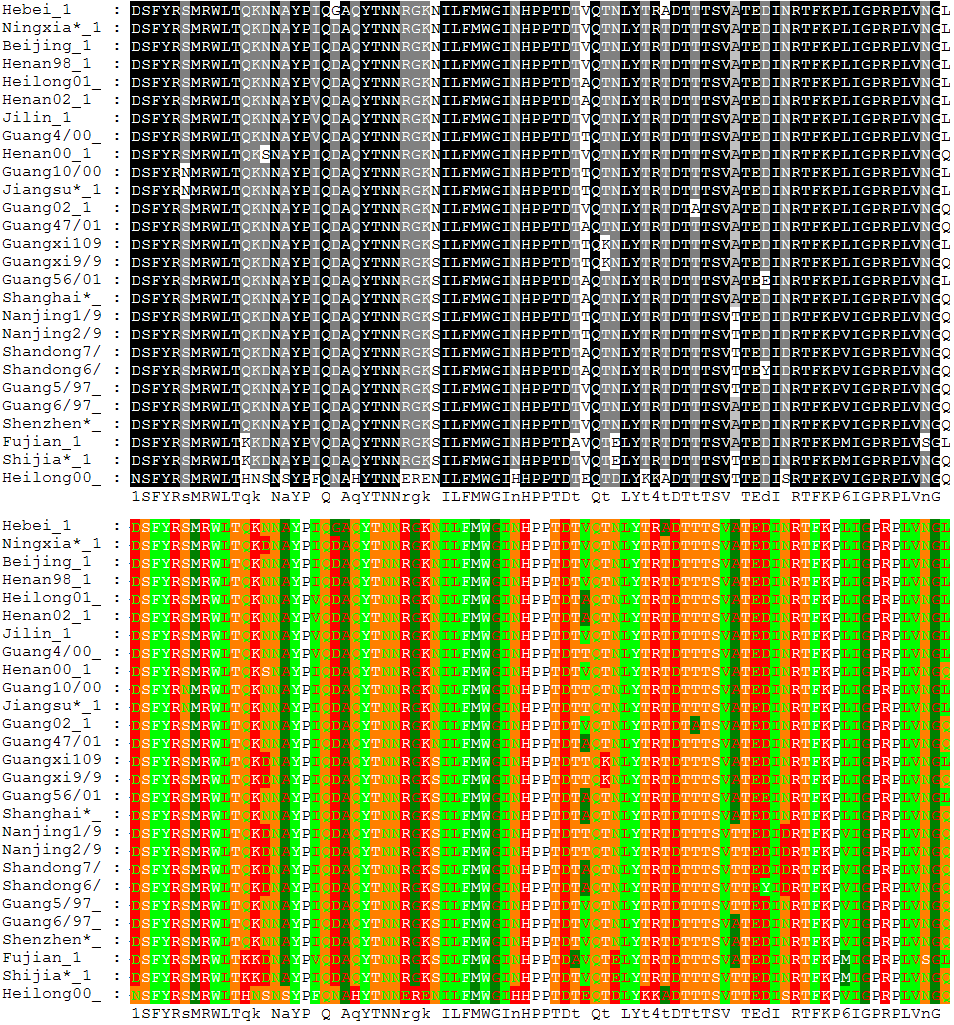

MSA of 27 avian influenza hemagglutinin protein sequences colored by residue conservation (top) and residue properties (bottom).

Phylogenetic use

Multiple sequence alignments can be used to create a phylogenetic treeLinks to an external site. This is made possible by two reasons. The first is that functional domains known in annotated sequences can be used for alignment in non-annotated sequences. The other is that conserved regions known to be functionally important can be found. This makes it possible to use multiple sequence alignments to analyze and find evolutionary relationships through homology between sequences. Point mutations and insertion or deletion events (called indels) can be detected.

By locating conserved domains, multiple sequence alignments can also be used to identify functionally important sites, such as binding sites, active sites, or sites corresponding to other key functions. When looking at multiple sequence alignments, it is useful to consider different aspects of the sequences when comparing sequences. These aspects include identity, similarity, and homology. Identity means that the sequences have identical residues at their respective positions. On the other hand, similarity has to do with the sequences being compared having similar residues quantitatively. For example, in terms of nucleotide sequences, pyrimidines and purines are considered similar. Similarity ultimately leads to homology in that the more similar sequences are, the closer they are to being homologous. This similarity in sequences can then go on to help find common ancestry.

Gallery

Below are examples of MSAs. Try to determine what the color coding indicates, how highly conserved regions are with the alignments, and if a consensus sequence is shown.

First 90 positions of a protein multiple sequence alignment of instances of the acidic ribosomal protein P0 (L10E) from several organisms. Generated with ClustalX.

TODO:

These are sequences being compared in a MUSCLE multiple sequence alignment (MSA). The sequence names (leftmost column) are from various louse species, while the sequences themselves are in the second column. Note the large insertion present in a single sequence.

Sequence logos

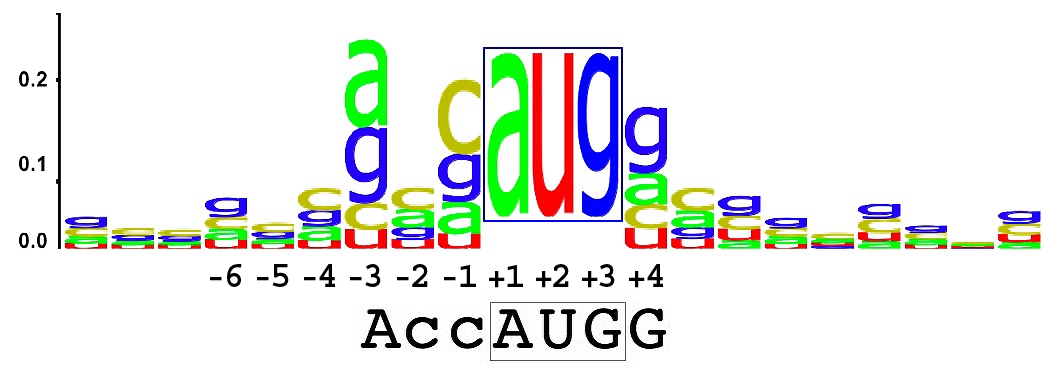

In bioinformatics, a sequence logo represents the sequence similarity of nucleotides (in a strand of DNA/RNA) or amino acids (in protein sequences). A sequence logo is created from a collection of aligned sequences. It depicts the consensus sequence and diversity of the sequences. Sequence logos are frequently used to depict sequence characteristics such as protein-binding sites in DNA or functional units in proteins.

A sequence logo consists of a stack of letters at each position, though sometimes one letter is much larger than the others. The relative sizes of the letters indicate their frequency in the sequences. The total height of the letters depicts the information content of the position, with more informative positions giving researchers more confidence in conclusions about a position in the logo.

A sequence logo showing the most conserved bases around the initiation codon from all human mRNAs (Kozak consensus sequence). Note that the initiation codon is not drawn to scale.

Sequence motif

The similarity in a sequence alignment or sequence logo may be due to relatively recent common ancestry or similar molecular function. Functionally similar sequences are termed sequence motifs. A sequence motif is a nucleotide or amino-acid sequence pattern that is widespread and usually assumed to be related to the biological function of the macromolecule.

Consensus logo

A consensus logo is a simplified variation of a sequence logo. A consensus logo is created from a collection of aligned protein or DNA/RNA sequences like a sequence logo. It conveys information about the conservation of each position of a sequence motif or sequence alignment. However, a consensus logo displays only conservation information and not explicitly the frequency information of each nucleotide or amino acid at each position. Instead of a stack made of several characters, denoting the relative frequency of each character, the consensus logo depicts the degree of conservation of each position using the height of the consensus character at that position.

A consensus logo for the LexA-binding motif of several Gram-positive species.

Acknowledgements

Some of this material was adapted with permission from the following sources:

Resources

- Singh, T. R., Saini, H., Comar Jr., M. (2024). Bioinformatics and computational biology: Technological advancements, applications, and opportunities. CRC Press.

- Hasija, Y. (2023). All about Bioinformatics: From Beginner to Expert. Elsevier.

- Chateau, A., & Salson, M. (Eds.). (2022). From Sequences to Graphs: Discrete Methods and Structures for Bioinformatics. John Wiley & Sons.

- Lesk, A. M. (2014) Introduction to Bioinformatics, 4th Ed. Oxford University Press.

- Jones, N. C., & Pevzner, P. A. (2004). An introduction to bioinformatics algorithms. MIT press.

- Durbin, R. (1998). Biological Sequence Analysis: Probabilistic Models of Proteins and Nucleic Acids.